“An artist is above all a human being, profoundly human to the core. If the artist can’t feel everything that humanity feels, if the artist isn’t capable of loving until he forgets himself and sacrifices himself if necessary, if he won’t put down his magic brush and head the fight against the oppressor, then he isn’t a great artist.” – Diego Rivera

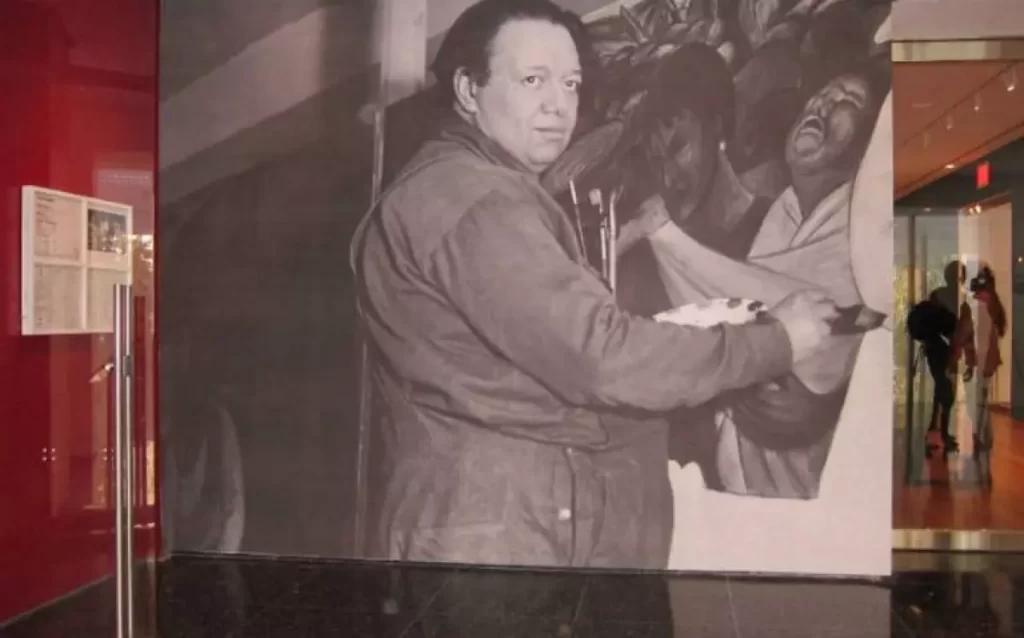

In the 1920s and 1930s, Diego Rivera had rightfully positioned himself as the leader of the mural movement in Mexico thanks to his massive and vibrant frescoes featuring powerful stories and historical narratives. In the course of his career, Rivera gained fame and followings for his distinctively thematic depictions of Mexican identity, nationalism, and politics. His grand-scale murals, created using the ancient fresco technique, added color and life to public spaces in Mexico and beyond. He was eventually commissioned to bring his unique vision to the United States, including New York City, Detroit, and San Francisco.

Between March 11th to July 31st, 2023, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas will present Diego Rivera’s America, an exhibition that began its journey at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) last summer. The exhibition brings together over 150 of Rivera’s works, including the 70 works that were housed at SFMOMA and other works borrowed from public and private collections. The exhibition will give audiences an in-depth examination of Rivera’s prolific career.

Understandably, Rivera’s most famous murals cannot be physically moved as they are rooted in their original homes. Instead, the exhibition displayed many of Rivera’s notable frescoes as large-scale projections. Rivera’s Pan-American Unity (1940), however, is a different story. Originally named Unión de la Expresión Artistica del Norte y Sur de este Continente (The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on this Continent), best known as Pan-American Unity is a jaw-dropping 22-feet high by 74-feet wide 10-panel “portable” fresco.

At the center of the Pan-American Unity is a towering figure of Coatlicue, the Aztec earth goddess. Rivera described his vision for the mural, saying “American art has to be the result of a conjunction between the creative mechanism of the North and the creative power of the South coming from the traditional deep-rooted Southern Indian forms.”The mural weighs more than 60,000 pounds and covers about 1,800 square feet. And despite its size and weight, it made the impressive journey from its permanent home at City College of San Francisco (CCSF) to SFMOMA. Moving Rivera’s Pan-American Unity required extensive planning and preparation that involved scientifically analyzing the requirements for extracting and moving the massive and fragile work of art. After its visit to SFMOMA, it will return to CCSF and be installed at its Performing Arts Center.

Making Murals to Communicate Cultural Identity, Political Conflict, and Socioeconomic Inequity

Rivera was born in 1886 and died at the age of 70 in 1957. Rivera led a life that resembled his frescoes – colorful and often controversial. Among his four wives was Frida Kahlo, another accomplished artist and cultural icon from Mexico. The name Rivera is often associated with another famous painter, Pablo Picasso, whom he was friends with. His works have been designated as national heritage and he would become one of the most influential artists of the 20th century over the course of his career.

Born in Guanajuato, Mexico as Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, Diego demonstrated at the early age of three that he was destined to be master of murals. His parents, upon discovering he’d drawn on the walls of their house, did not scold him. Rather, they encouraged his creativity by installing chalkboards and canvases on the walls. At only 10 years old, Rivera was already formally studying art at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City thanks to a government scholarship granted by the governor of Veracruz. However, Rivera’s political-charged consciousness also began at an early age. And in 1903 at the age of 17, he got kicked out of the academy for joining a protest against President Diaz, Mexico’s president at the time.

In 1907, Rivera moved to Europe to expand his art scene, experimenting and embracing styles like Cubism and Post-Impressionism. By 1917, he had distanced himself from those avant-garde movements. Rivera moved from Madrid, Spain to Paris and thanks to the opportunity to travel to Italy, he began studying the Renaissance frescoes. In 1921, he returned to Mexico with a clear understanding of not only his medium of choice, but also how he wanted to convey his messages through art.

On his return to Mexico, Rivera painted Creation (1922) for the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, his first government-commissioned mural. The composition explored the concept of mestizaje or the mixing of different ethnic and cultural groups throughout Mexican history in an effort to eliminate racial conflict and promote social progress and national unity. The massive allegorical mural contained religious and mythological motifs, including depictions of Adam and Eve, symbols representing the Divine Trinity, Apollo and the nine muses, and the Christian virtues. Rivera demonstrated his skill in the classical renaissance style through the encaustic painting – though he would later admit that he did not like that he used a technique that was too Italian. It took Rivera a year to create the artwork as it spanned over a thousand square feet and the figures he depicted stood over 12 feet high.

Between 1929 and 1935, Rivera would create one of his most famous and monumental works – the Epopeya del pueblo mexicano which covers the walls of the National Palace of Mexico City. The colossal mural occupies a total surface area of 2960 square feet. It covers three different walls, each with contents that convey its own dialogue. The themes are arranged in chronological order, representing Mexico’s colonial past, present, and future. It is understandable that Rivera would have taken six years to complete the breathtaking mural as it is meticulously detailed and painstakingly executed.Rivera did, however, also create other works during that time. Between 1932 and 1933, Rivera worked on the Detroit Industry Murals, which consisted of 27 panels. While Rivera often employed assistants to help him accomplish his projects, Rivera was said to have lost 100 lbs when he worked on the panels due to the exhausting work schedule. The mural depicts laborers at Ford Motor Company and the relationship between man and machine, which is ironic because of the theme of labor.

Rivera’s Bold Visual Style and Provocative Narrative

Over the course of Rivera’s prolific career, he created numerous drawings and paintings. In 2018, his Los Rivales (1931) painting sold for a little under $10 million. It can be argued, however, that the only reason that Rivera’s works have not sold for more is because his most famous and recognizable works are simply unavailable for purchase. The institution that commissioned the frescoes is unlikely to let them go due to their placement, iconic status and cultural significance, and will instead preserve the works for the future generations. In 2014, one of Rivera’s most celebrated murals, Detroit Industry Murals (1932-1933) was designated by the Department of Interior as a National Historic Landmark.

For Rivera, frescoes provided the ideal medium for expression; murals, much like his character, were larger-than-life and demanded attention. Because frescoes were accessible to the public, they provided Rivera with a grand stage to communicate the social and political subject matters that engaged and often enraged him.However, many of Rivera’s murals were commissioned and his patrons had specific visions of the themes – some of which Rivera didn’t always agree with. For Creation (1922), Rivera stunningly executed visuals of Christian values and virtues. Rivera, though, was an atheist who considered religion to be a “form of collective neurosis.” And his Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (1946-47) mural includes an inscription that reads, “God does not exist.” The mural remained hidden from the public until he agreed to remove the controversial writing.

When the politically-conscious Rivera allowed his independent nature to take over, his concepts resulted in depictions that caused quite a furor. But as seen in the works that have endured, Rivera was able to defend his choices and most of his murals remain uncensored to this day. He was not so lucky, however, when he was commissioned by the Rockefellers in 1933 to paint a mural for the Rockefeller Center in New York City. The artist refused to remove the May Day scene which had a clear image of Vladimir Lenin leading the demonstration of workers. The Rockefellers ordered Rivera to stop his work and the painting was reportedly destroyed. Ironically, over eight decades later, it would be members of the Rockefeller family that would help strengthen Rivera’s legacy by paying close to $10 million for Los Rivales (1931), setting the record for the highest price paid at auction by a Latin American artist at that time.

The government of Mexico has declared Rivera’s works as monumentos historicos (historical monuments) and his murals are protected by the nation for their cultural significance. As an influential 20th century Mexican artist, Rivera’s legacy lives on in his contributions to the art and culture of Mexico, and to the world, as his murals are now seen as a representation of Mexican identity around the globe.