In June 2023, at Sotheby’s London, Gustav Klimt’s Lady with a Fan (Dame mit Fächer) (1917) became the most expensive artwork ever sold at a European auction, fetching $108.4 million (£85.3 million). Now, a significant painting by the legendary Austrian painter has resurfaced at 2025 TEFAF (The European Fine Art Fair) in Maastricht — a piece that had been missing for decades.

The painting, offered by the Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Gallery, was created by Klimt in 1897 and depicts Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona, an Osu prince from what is now Ghana. With a current valuation of $16.4 million (€15 million), the painting itself has an intriguing history, and its provenance presents even more historical twists.

In 1897, Klimt and fellow artist Franz Matsch were commissioned to paint the prince. The fact that Klimt’s version remained unsigned suggests that the client preferred Matsch’s interpretation. The painting appeared at Vienna’s Samuel Kende auction house in 1923 and was later owned by Ernestine Klein, who exhibited it in Klimt’s 1928 memorial exhibition. Klein fled to Monaco in 1937 during the Nazi occupation of Austria, at which point the painting disappeared. It resurfaced in 2021 when a collector brought it to the gallery in poor condition, described as “heavily soiled” with a barely visible estate stamp. Klimt scholar Alfred Weidinger, who had been searching for this specific work for two decades, confirmed its authenticity.

The composition holds particular significance as it was painted in the same year that Klimt, along with other visionary artists, founded the Vienna Secession. Klimt led this revolutionary art movement that aimed to dismantle artistic conventions and the rigid traditions enforced by the Association of Austrian Artists. The portrait is crucial as it marks Klimt’s transition towards the more decorative elements that would later characterize his work and heavily influence the Vienna Secession movement. Moreover, the recent emergence of the painting signifies a broader market shift towards recognizing the full spectrum of Vienna Secession artists. This includes pioneering figures who existed in the shadow of Klimt’s formidable legacy. The shift particularly emphasizes female artists, who faced both competition from Klimt’s prominence and historical marginalization.

Celebrating the Lesser-Known Artists of the Vienna Secession

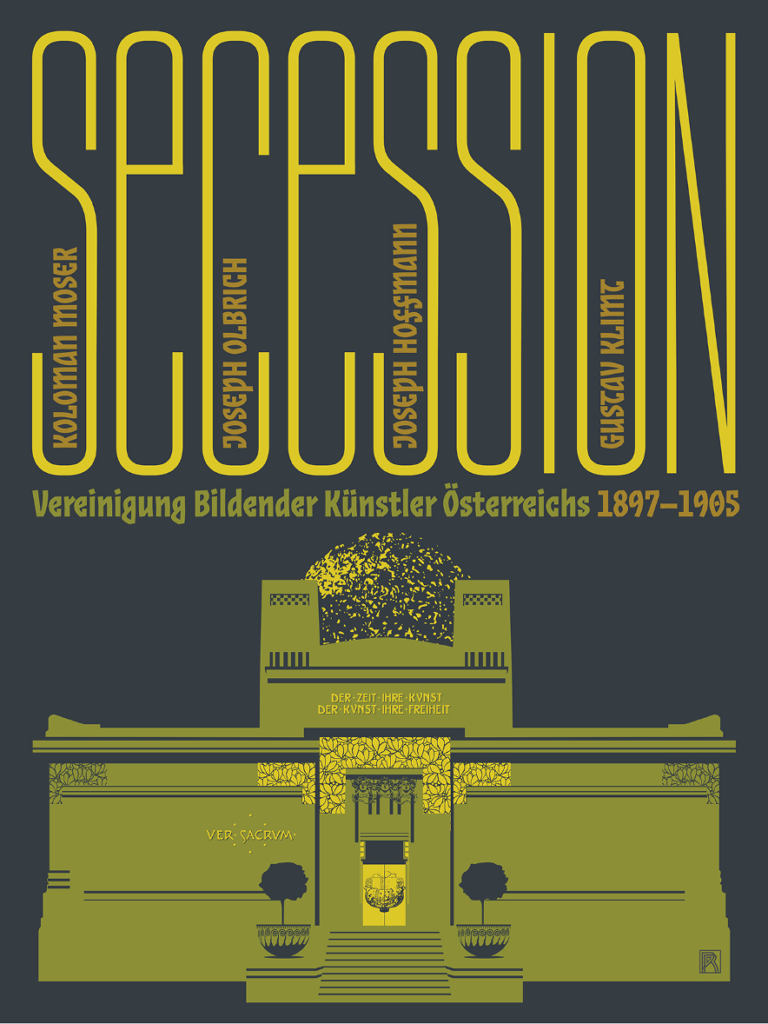

Inspired by the Art Nouveau movement, the Vienna Secession was a bold declaration of independence, born from rebellion against the artistic status quo. The movement paved the way for avant-garde expression, embracing innovation. Dissatisfied with the dominating conventions of the Viennese art scene, radical artists broke away, even erecting the Secession Building in Vienna where the movement’s foundational belief “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit (To every age its art, to every art its freedom)” is inscribed.

Despite their diverse practices, they united in their collective push towards modernity and a broader questioning of identity and societal norms. Driven by an ethos resonating deeply with the cultural and intellectual atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Vienna, the movement invigorated the artistic community by embracing modernist principles, drawing from international influences, and fostering a dialogue spanning disciplines — architecture, design, painting, and beyond.

The Secessionists were renowned for their stylistic innovation and bold experimentation, characterized by modern geometric forms, flattened decorative patterns, and the integration of diverse artistic disciplines into what they termed “Gesamtkunstwerk” — a total work of art. This holistic approach harmonized architecture, interior design, and the fine arts to create an immersive aesthetic experience.

Beyond the towering figure of Klimt, the Vienna Secession was shaped by a diverse collection of talented artists. Koloman Moser, a founding member of the movement, played a fundamental role in crafting the Secession’s visual identity with his graphic designs and illustrations. Moser, along with Josef Hoffmann, co-founded the Wiener Werkstätte. Hoffmann, through his revolutionary approach to form and function, pioneered a distinctly austere geometric style. His work is characterized by geometric forms, notably recognized in his iconic square-grid designs.

Meanwhile, Carl Moll, an influential leader and painter, was celebrated for his innovative use of light and contributed to the movement’s expansion and diversification. He managed the group’s exhibition program, skillfully organizing influential exhibitions like the landmark 14th Secession Exhibition featuring Klimt’s Beethoven (1902). The works of Max Kurzweil, a painter and printmaker, embodied the movement’s innovative flair, combining naturalistic elements with decorative style in his sophisticated portraits. He served as the co-editor of Ver Sacrum, the Secession’s artistic journal. Thanks to his technical expertise in printmaking, he helped establish the journal’s high quality of visual presentation. Architect Josef Maria Olbrich’s profound contribution to the movement was the Secession Building. The structure, completed in 1898, is known for its distinctive golden dome remains an iconic testament and physical manifesto of the movement’s ideals.

The Female Legacy of the Vienna Secession: A Shift in Recognition and Market Dynamics

The Vienna Secession, known for its radical departure from conventional art practices, unfolded during an era when female artists navigated a patriarchal society that limited their official participation. Despite these challenges, many women found creative avenues to express their artistry, though their contributions were often overlooked in broader art historical discourse. In recent years, the long-overdue recognition of these innovative female contributors has highlighted their historical significance and led to shifts in the art market.

Broncia Koller (1863-1934)

Broncia Koller is a significant figure among these artists, with her work contributing to the reassessment of female artists’ roles in the Vienna Secession. Known for her bold use of color harmonies and psychological depth, Koller developed a distinctive style by incorporating the decorative elements distinct to the Secession into domestic scenes. Young Woman in Front of a Bird Cage (c. 1907) and Silvia Koller with a Bird Cage (1907-08) are two pieces that exemplify her ability to convey intimate domestic scenes and represent her use of vivid color palettes. Today, her artwork has been repeatedly offered at auctions, with realized prices of as much as $55,462.

Elena Luksch-Makowsky (1878-1967)

Elena Luksch-Makowsky is noted for her integration of Russian folk-art traditions with the ornate and symbolic features typical of Secession aesthetics, creating a distinctive style that resonated with both Russian and Central European audiences. Focusing mostly on portraits of women and children, her works are imbued with psychological and emotional depth.

The Neue Galerie’s acquisition of her works signals her rightful recognition as a contributing force in the movement. Vienna’s MAK (Museum of Applied Arts) has been pivotal in preserving and showcasing works associated with the Vienna Secession. With Luksch-Makowsky’s “Mother and Child” relief as part of the collection at the MAK, the relevance of her contributions to the movement is highlighted. Her most acclaimed works include the “Adolescentia” series (1902-1903), which depicts themes of female growth and transition.

Teresa Feodorovna Ries (1874-1956)

Teresa Feodorovna Ries is recognized for her dramatic marble sculptures that challenged artistic and social norms. Her often controversial works depicted themes considered provocative at the time. Lucifer (1897), in particular, caused quite the stir for its portrayal of a sensuous figure and exploration of the darker aspects of human nature and mythology. Lucifer won her the Karl Ludwig Medal at the “Jahresausstellung des Künstlerhauses” (Annual Exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus) that year. Ironically, it was the only sculpture with a male subject presented at the exhibition.

Witch at Her Toilette (1895) is perhaps her most famous piece due to its daring subject matter and bold representation of a witch preparing for a Sabbath. Witch at Her Toilette is now part of the Wien Museum’s collection in Vienna, illustrating her significant role in defining the Vienna Secession and her appeal to contemporary collectors.

Ilse Twardowski-Conrat (1848-1938)

Ilse Twardowski-Conrat’s works in portrait sculpture and distinct portrayal of human emotion and form distinguished her contributions to the Secession and modernist circles. Empress Elisabeth‘s portrait bust (c. 1907) exemplifies Twardowski-Conrat’s sculptural style, which incorporated clean lines and simple modernist forms into the traditional format. She was celebrated for her ability to capture nuanced human expressions and emotion while demonstrating a deeply studied execution of human anatomy. She created lifelike portrait busts and figurative sculptures with names that were unfortunately not widely documented, emphasizing the historical challenge of preserving records for many female artists of that time.

Helene Funke (1869-1957)

Modernist painter Helene Funke’s expressive experimentation with color is evident in dynamic compositions like Träume (1913). She played a pivotal role in promoting female artists, often exploring themes of femininity and nature. Her approach to abstract portraiture has garnered recognition and interest in the art market, with her works preserved in collections at institutions like the Belvedere Museum in Vienna. The recently sold painting “Breton Girl” (1906-1913), an oil-on-canvas piece, fetched €15,000 (approximately $16,000). Another piece, “Still Life with Fruit” (1919), sold for €42,000 (about $46,000), exceeding its estimated value.

Conclusion: Broadening the Narrative of the Vienna Secession

Gustav Klimt’s recently resurfaced work has reignited interest in the Vienna Secession but also led to a broader recognition of the diverse artists who contributed to this radical movement, highlighting an exciting shift in the art world. This promising appreciation not only reframes the contributions of male figures but also elevates the long-overlooked achievements of female pioneers. Reflecting on the Vienna Secession, we remember its core mission: challenging artistic norms and breaking free from the restrictive traditions of its time. It boldly stood for “To every age its art, to every art its freedom,” advocating for a fresh wave of creative expression. Recognizing that spirit today means celebrating not just iconic names like Klimt but also those artists who may have been eclipsed or sidelined due to societal norms. By doing so, we continue to uphold the movement’s original mission of championing creativity and freedom in the arts.