The stunning exhibition “Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 B.C.E.-400 C.E.” has been unveiled at the Metropolitan Museum. Curated by John Guy, the groundbreaking logistical and diplomatic venture took a decade to bring to fruition as it assembled over 125 ancient Indian art artifacts under one collection for the first time. The ambitious and unparalleled exhibition serves as a testament of the history and influence of Buddhism, the practice that originally drew from existing animist nature cults to become one of today’s most powerful religious and cultural forces.

The exhibition emphasizes the power of international cultural collaboration as demonstrated through the extensive efforts to bring the valuable antiquities together. The exhibit required securing antiquity loans from five countries. Because some of the pieces had never been on display outside India, the Met also grappled with artifact repatriation issues and participated in negotiations with numerous entities, including the central government, the Ministry of Culture, the Archaeological Survey of India, the National Museum, and six state governments in India.

Bringing the entire collection to U.S. soil was an impressive feat as it required transporting hundreds of rare antiquities that collectively weigh 36,737 lbs. from India to the Met. Curators faced challenges as they navigated weather and logistical complexities. Those challenges were further exacerbated by the pandemic, which replaced many personnel that were involved in the initial talks and no longer associated with their organizations by the time planning resumed.

The curator of the exhibition also extends the scope of the historical narrative by not only capturing the evolution of early Buddhism in India but also demonstrating the expansion and influence of the faith that extended to Southeast Asia, China, and Japan.

Early Beginnings: A Story of Symbols and Aniconic Art

Siddhartha Gautama was a religious teacher born in 564 BCE. According to legend, he was a Hindu prince who renounced his wealth and position to seek enlightenment and lead a life that was free from ignorance, craving, and suffering. Centuries after Gautama’s death, he would come to be known as “Buddha,” which translates to the “Awakened One” or the “Enlightened One,” and his teachings would be compiled by followers of the Buddhist community.

In its early stages, Buddhism was a practice centered on nature and reflected a connection with spiritual reverence for creatures and beings. And the art forms that emerged centuries following Buddha’s death would comprise a vast and intricate tapestry of devotion, philosophy, and beauty. Initially, the art would represent Buddha symbolically due to the tradition’s aniconic character and discouragement of idol worship. Therefore, early depictions of Buddha were meant to focus instead on his wisdom and teachings and would often depict an empty throne of footprints.

The Footprints of the Buddha, or “Buddhapada,” became one of the earliest and most symbolic representations of Buddhist art. Often decorated with Dharmachakra (the Wheel of Dharma) and other auspicious symbols, they served as physical reminders of the Buddha’s presence on earth and his path to enlightenment. Much of Buddhist art has hidden or hard-to-spot details that hold symbolic significance. The parasol or umbrella, for example, symbolizes royal dignity and protection from the heat of suffering, passion, and desire.

Other aniconic symbols such as the Bodhi tree, the lotus flower, and mandalas were often used in Buddhist art to help followers focus their minds. The beloved lotus grows in muddy water, yet blooms beautifully above the surface, untouched by the murky mire below – making the lotus a symbol of purity, spiritual awakening, and resilience. And as complex diagrams, mandalas are often used in Buddhism to aid meditation and visualization. In Buddhist art, they represent the universe, its divine deities, and metaphysical aspects of life. And you’ll see them in wall paintings, scrolls, and three-dimensional statues.

Spiritual Communication Through Hand Gestures and Serene Expressions

The 1st century CE marked a crucial transition in Buddhist art with the development of physical depictions of the Buddha. Buddha’s serene expressions and distinctive physical attributes like the ushnisha and elongated earlobes in the artwork were intentional. The ushnisha is the bump on the top of the head which symbolizes wisdom while elongated earlobes signify a noble life that renounces mundane attachments, making these representations of Buddha as depictions of reverence and tools to communicate Buddhist philosophy.

Buddha’s expressions, which are often characterized by half-closed eyes and a faint smile, are meant to represent peace and composure. The positions of the Buddha’s hands, or mudras, also hold significant meanings. For example, the touching of the earth (Bhumisparsha mudra) represents the moment of Buddha’s enlightenment, while a hand raised in the stop gesture (Abhaya mudra) symbolizes fearlessness and protection.

The Influence and Aesthetic Revolution of Buddhist Art

The inception of figurative depictions of Buddha were introduced predominantly under two distinct schools: the Gandhara School and the Mathura School.

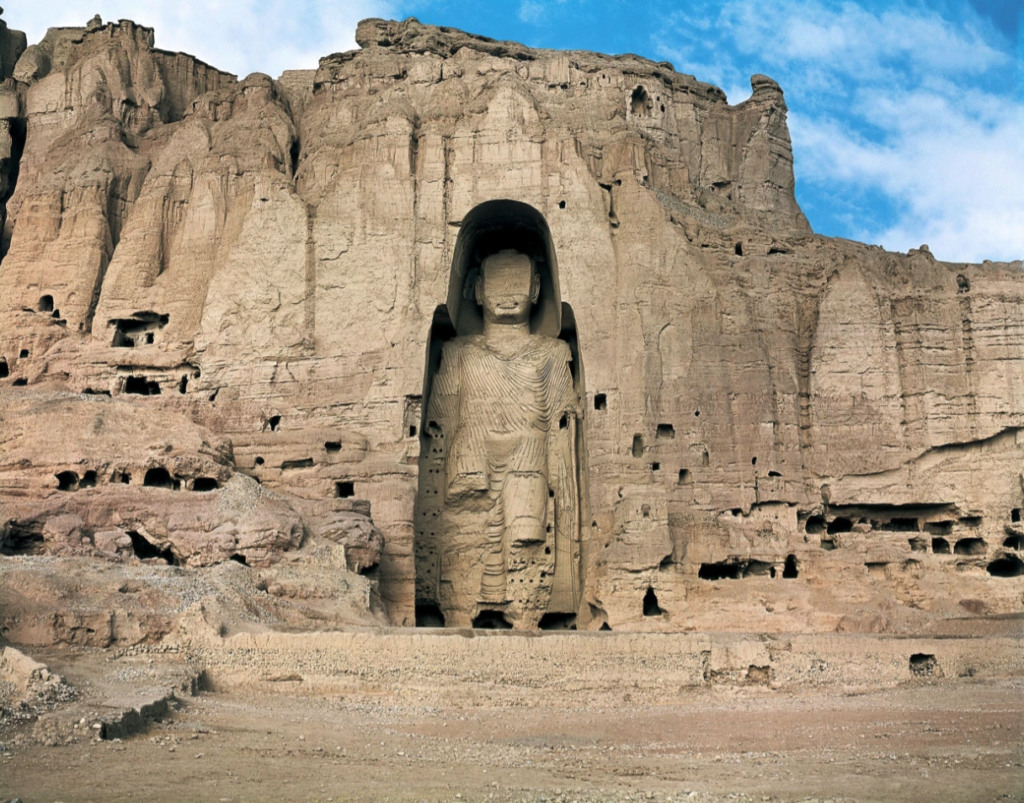

Influenced by Greco-Roman artistic ideals, the Gandhara School, located in today’s Pakistan and Afghanistan, reflected the confluence of Greco-Roman and Indian art. And statues of the Buddha from this period bear a striking resemblance to Greek gods with flowing robes and curly hair. The more intrinsically Indian Mathura School, on the other hand, favored a more indigenous style and depicted Buddha as a nearly naked monk with tightly curled hair and long ears – with the near absence of clothing meant to symbolize the renunciation of worldly luxuries.

As Buddhism spread from India to various parts of Asia, it assimilated local artistic traditions and themes, leading to the emergence of distinct regional styles. The world would be introduced to new forms of Buddhist art from Tibet, Thailand, Japan, China, and Korea, resulting in sublime expressions of Buddhist philosophy in art.

In Japan, the advent of Zen Buddhism introduced minimalistic aesthetics and intuitive expressions, which would stand in stark contrast to the styles found in Tibetan Buddhist art, where deities are represented with intricate details and vibrant colors. And in China, Buddhism would be represented in the form of monumental Buddha statues.

And in Tibetan Buddhism, thangkas, scroll paintings, and mandalas became central to their practice, resulting in intricate artworks that were often accompanied by statues of wrathful deities. These pieces were often used as meditations aids as the detailed works allowed the viewer to immerse themselves in Buddhist teachings and cultivate mindfulness and concentration.

Getty Images file. | Source: nbcnews.com

Iconic Examples of Buddhist Art

Buddhist art is rich and diverse, represented mostly in sculpture, paintings, and temple architecture. Traditional Buddhist art is often anonymous, as it is considered a form of meditation and devotion rather than an opportunity for individual self-expression or fame. Therefore, the most iconic examples of Buddhist art today are often not accompanied by an artist’s name.

In the rocky cliffs of the Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan, once stood two gigantic Buddha statues, carved in the 6th century. Standing at an impressive 180 ft. and 121 ft. respectively, these statues were the largest standing Buddha carvings in the world. They embodied the classical blended style of Gandharan art – fusing Greek, Roman, and Indian artistry. Sadly, the statues were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

Located in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra, India, the Ajanta Caves are an ensemble of about 30 rock-cut Buddhist caves. Dating from the 2nd century BCE to 480 CE, they represent two significant periods of Buddhist art — the Hinayana phase, where Buddha was depicted symbolically, and the Mahayana phase, where Buddha was personified.

In Japan, the Daibutsu, the Great Buddha statue at Todai-ji Temple, is a colossal bronze representation of Vairocana Buddha, built in the 8th century. Standing nearly 50 ft. tall, it is the largest bronze Buddha statue in Japan. And in the high-altitude monasteries of Tibet, the Thangka or scroll paintings, often framed in silk, portray Buddhist deities, scenes from Buddha’s life, and complex cosmological models. They serve as meditation tools, helping practitioners visualize deities and understand the intricacies of Buddhist philosophy.

The 9th-century Borobudur Temple in Central Java, Indonesia, is the largest Buddhist temple in the world. The Buddhist community celebrates the structure as the practice’s vision of the path to enlightenment. Borobudur, composed of nine stacked platforms, is adorned with over 2,600 relief panels and 504 Buddha statues. And it is believed that as a pilgrim moves upward through the monument’s levels, they metaphorically journey through the realms of Buddhist cosmology to reach “Nirvana” at the top.

The Met’s “Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 B.C.E.-400 C.E.” will run July 21st–November 13th, 2023, and is free with museum admission.