The term ‘life’ as used in art is something not to be held in contempt, for it applies to all of its existence, and the province of art is to react to it and not to shun it. – Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper was an American realist painter who died of natural causes on May 15th, 1967 – over five decades before the world was disrupted by the wrath and chaos of COVID-19.

The global pandemic forced people into isolation, quarantining themselves in their homes to prevent the spread of disease as well as maintain their personal health. If we did go out in public, we deliberately put physical space between ourselves and others. Stores shut their shutters and closed their doors. Spaces that were typically crowded were empty. Travel was restricted and borders were closed. And just like that, the streets, buildings, and even people looked like the subjects of an Edward Hopper composition.

Hopper is known for his paintings of trains, highways, hotels, motels, theaters, restaurants, and offices. And while these are locations that are typically occupied by people, he always painted them empty or close to it. When he was not painting a lone structure or semi-deserted public place, he painted otherwise ordinary people engaging in mundane activities. And if they weren’t lone figures, they were a collection of human subjects; however, there was nothing collective about their mutual presence. And very rarely did the people in his works appear to deeply engage or even acknowledge the other.

Hopper’s work emphasizes a certain moodiness, evoking feelings of unwelcomed solitude and therefore, isolation. Despite being compositions created between the 1920s and 1960s, Hopper’s work is eerily reminiscent of what the world looked like at the height of the lockdown brought on by the coronavirus. And his paintings almost feel like a foreboding of the social distancing we would at first be forced to practice but later choose willingly.

Addressing American Society’s Isolation and Alienation

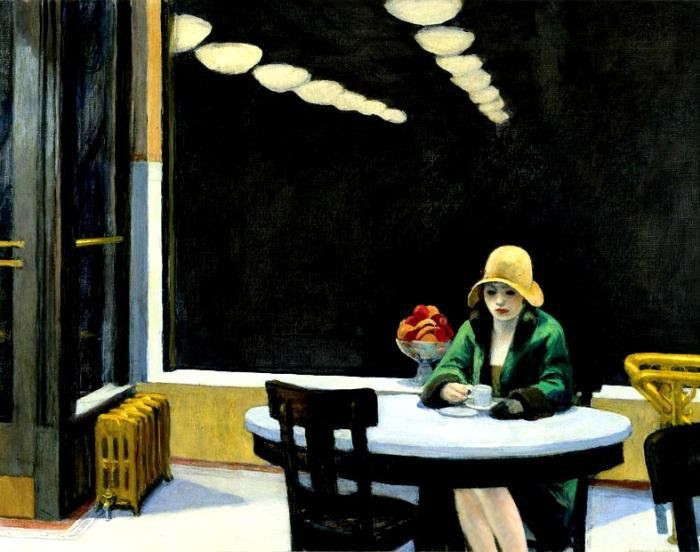

The ongoing pandemic is not the first time that Hopper’s work has been used as a symbol of society’s loneliness. In 1995, Edward Hopper’s Automat (1927) painting graced the cover of Time magazine, along with the cover line “20th Century Blues” and “Stress, anxiety, depression: the new science of evolutionary psychology finds the roots of modern maladies in our genes.”

The painting depicts a well-dressed young woman sitting at a table, staring absently into the cup of coffee she holds. It is night. She has removed only one glove, alluding to her distracted or weary state. Her legs are crossed. And she sits alone in an automat, those fast food establishments where people can buy hot food from a vending machine. Her expression may be ambiguous; however, the whole composition argues a certain sense of longing and seclusion.

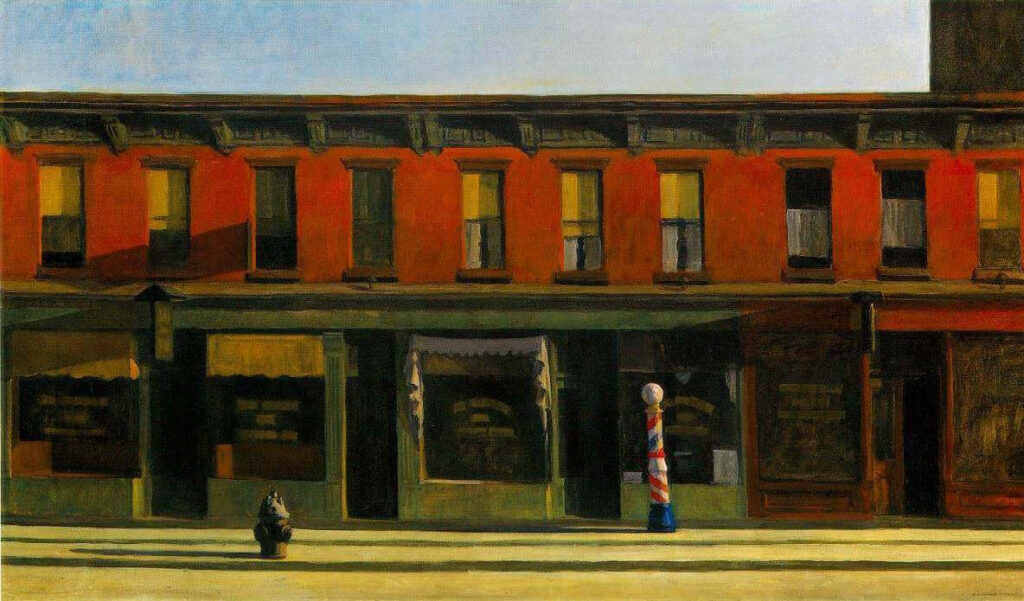

In Early Sunday Morning (1930), we see a street of small businesses. There are no people in the composition. One may argue that the work’s title and Hopper’s dramatic use of light and shadow aim to stage the scene during the earliest time of day when shopkeepers and customers have not yet awoken. Somehow, it hits us differently when we consider that New York is the “city that never sleeps” and scenes like these are rare. It would appear that Hopper was intentional in his portrayal of emptiness, both physically and emotionally. And we can’t help but look at the painting and recognize that the lack of human activity is not necessarily quiet and peaceful, but rather, abandoned, ignored, and forgotten – unnervingly familiar to what once bustling city shops suffered during the height of the pandemic.

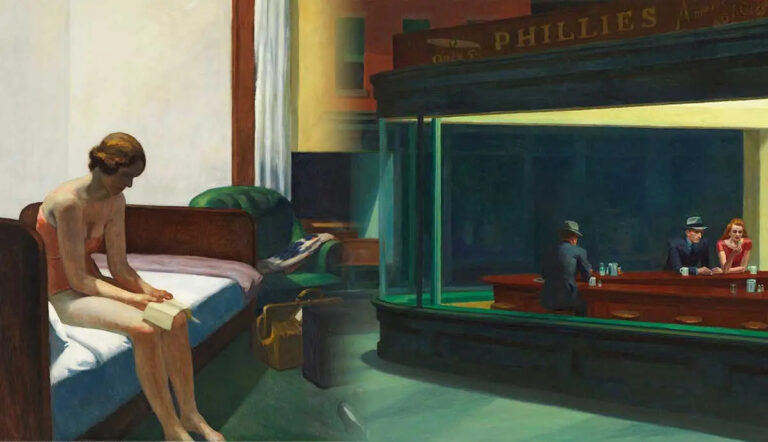

In one of Hopper’s most recognizable works, Nighthawks (1942), we see four people in an illuminated diner, presumably late at night while the rest of the world sleeps. The neighboring shop is closed and dark. The only notable interaction is between the well-dressed gentleman and the server. And the lack of emotion and connection between the patrons sitting at the bar only further exemplifies the emotional distance. When asked if Hopper purposely used his subject matters and themes as symbols of human isolation, he denied it. However, with Nighthawks, Hopper acknowledged that he “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

Makings of One of the Most Recognizable American Realist

Edward Hopper was born on July 22nd, 1882 in Nyack, New York State, a quaint Hudson River town about forty minutes from the city. Demonstrating talent in art early in his life, his parents provided him with the encouragement and resources to pursue his creative interests. At just 10 years old, he completed his first signed drawing and by 13, Hopper had created his first signed oil painting.

While Hopper expressed an interest in architecture at a young age, he never pursued formal studies in the vocation. Instead, he channeled his fascination for urban structures through his work. Hopper studied at the New York School of Illustrating before transferring to the New York School of Art and Design, where he would work under “the most influential teacher,” Robert Henri – the painter credited for paving the way for the development of twentieth-century American Realism.

In 1906, Hopper left for Paris to study the art scene. And while he made repeat travels to the city, along with trips to London, Berlin, and Amsterdam, Hopper revealed that Europe had no influence or impact on his work. He returned to New York City where he reluctantly solicited for projects to support himself. Still struggling to define his aesthetic, Hopper would travel, actively seeking inspiration.

Hopper would not sell his first painting until 1913 at the age of 31, which sold for $250. Two years later, he would transition to etching and create urban scenes. It wasn’t until 1923 that Hopper’s life and career took an upward turn. He reconnected with Jo Nivison, a neighbor, fellow artist, and former student of his old teacher Robert Henri. They would marry the following year – the same year that his solo show sold out. Ironically, he found success during the Great Depression, a time when the US economy and consequently, society, suffered severely.

Hopper was described as stoic and introverted, a personality which may have inclined his choice to depict isolated spaces and vulnerable narratives. However, Hopper was also characterized as obsessive and violent. And his marriage to Jo Nivison was turbulent and competitive. Despite an abusive relationship, the two would remain married for over four decades. Hopper would often use his wife as his model. His lifelong muse was also his only partner. And it became evident through Nivison’s deeply documented diaries that her existence and influence played a pivotal role in the artist that Hopper ultimately became.

In 1929, Hopper was included in the exhibition Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans by the Museum of Modern Art. And by 1931, Hopper was recognized by major museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. While many still felt the sting of the recession, there were patrons still willing to pay thousands of dollars for Hopper’s work.

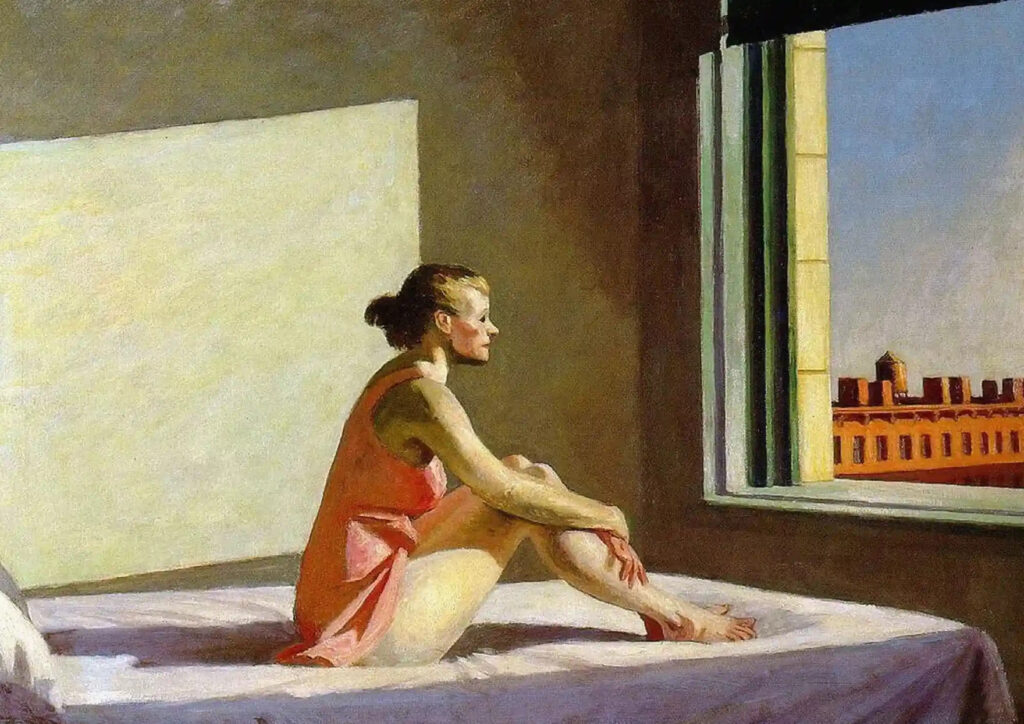

Staying committed to his personal style for the rest of his career, Hopper would create his most recognizable works, including Gas (1940), Office at Night (1940), Rooms By The Sea (1951), and Morning Sun (1952). The most expensive work by Hopper to ever sell at auction was Chop Suey (1929), which fetched a record-breaking $92 million sale.

Edward Hopper’s New York – October 19th, 2022 – March 5th, 2023

Edward Hopper’s New York at the Whitney Museum of American Art will be the first of its kind, focusing intently on Hopper’s enduring relationship and fascination with the city, which spanned almost 60 years. The curation will offer audiences an examination of Hopper’s life and work.

When Hopper’s wife died shortly after him, she donated her husband’s artwork to the Whitney Museum. The Whitney currently owns more than 3,100 of Hopper’s works. The exhibition will feature over 200 of Hopper’s works, some of which have been loaned from private and public collections.