Opportunities to lay claim to an iconic masterpiece by the globally-renowned Gustav Klimt are rare, as most of his golden treasures are guarded by the museums and collections with the privilege to house them.

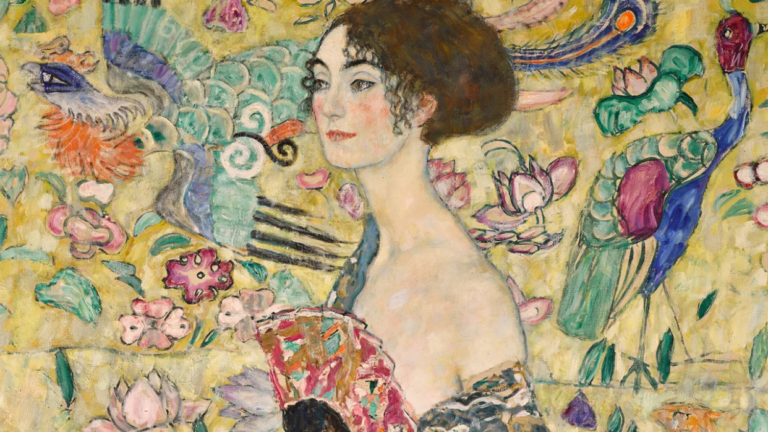

And that is precisely why Klimt is back in the limelight as his ethereal masterpiece Dame mit Fächer (1918) dazzled on stage at Sotheby’s of London. On June 27th, 2023, the Austrian symbolist painter’s “last” masterpiece sold for a record-breaking $108.4 million – almost $20 million more than the rumored $80 million that experts predicted.

Dame mit Fächer, which translates to “lady with a fan” is an enchanting and elegant blend of color and pattern – a demonstration of visual poetry that proves that every stroke, shape, and hue plays a part. The titular lady of the piece captures its audience with a distant and demure gaze rather than a direct stare. There’s a hint of smile on her lips, which elevates her sense of mysterious serenity. A stunning gold and blue robe that drips with opulence thanks to its intricate Byzantine-like patterns gracefully exposes her bare shoulder. The fan she holds in her hand, with its playful swirls of colors, is a character in its own right. While the background is a kaleidoscope of shapes and colors, it doesn’t upstage the lady but rather, lends richness and depth to the composition.

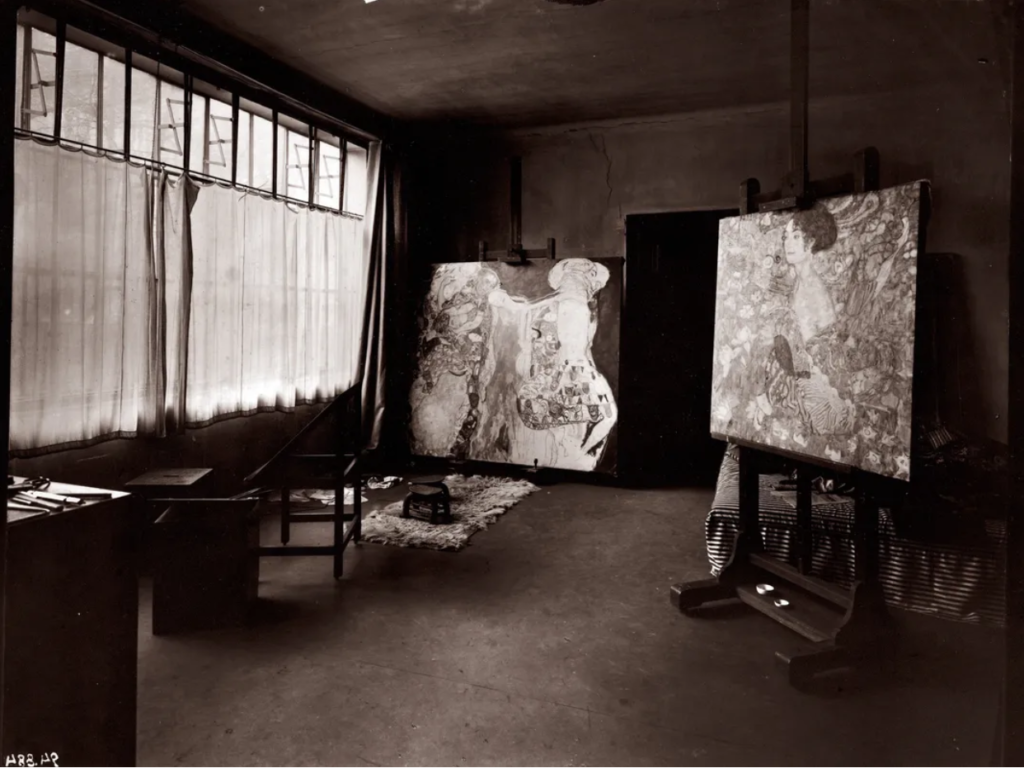

The masterpiece is the last known testament of Klimt’s extraordinary craft before the artist bid farewell to the world in 1918. Erwin Böhler, a good friend of Klimt’s, became the custodian of this painting shortly after the artist’s death. From there, the artwork made its journey into the hands of an art collector, ending up with an undisclosed family for $11.6 million thanks to Sotheby’s New York auction in 1994.

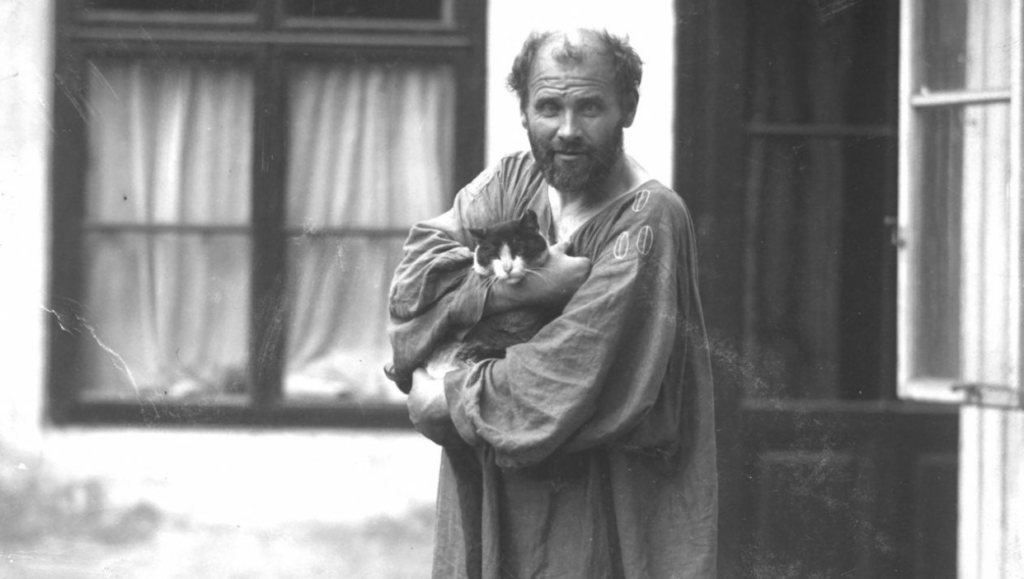

But what set Klimt apart from his contemporaries and allowed his legacy to endure over a century after his final painting and passing? What made Klimt – a man who has been quoted to say “there is nothing that special to see when looking at me” – an enduring testament to the power of artistry and innovation?

Humble Origins and Artistic Awakening

Born in Baumgarten, a suburb of Vienna, on July 14, 1862, Klimt was the son of immigrant parents and the second of seven children. His father was a gold engraver and because opportunities were scarce for immigrants, Klimt’s family lived in poverty for most of his childhood.

When Klimt was about 14 years old, he had the opportunity to study at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts where he received training as an architectural painter. He began his professional career as a painter of interior murals and ceilings. By 1888, Klimt had gained recognition for his contributions to art, even receiving the Golden order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria.

Initially, Klimt’s art stayed true to the traditional art styles he was formally taught at school. However, a turning point occurred when he was commissioned to paint a series of murals in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. His murals were met with criticism, sparking rebellion in Klimt that motivated him to depart from conventional norms.

He co-founded the Vienna Secession, a collective of artists who advocated “Art for Art’s sake,” dissenting from conservative hierarchy that valued historical paintings over all other forms of art. The daring move set the stage that would ultimately position Klimt as an emblematic figure in the art movement that would depart from academic art and move towards a more experimental, avant-garde approach.

Over the decades, Klimt would push the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in art and set himself apart from his contemporaries through his use of symbolism and allegory. His works stood out for their ornamental extravagance and bold eroticism that were executed with technical prowess. He depicted themes of love, death, and female beauty, communicating a unique aesthetic vision that exposed human emotions. His works would attract controversy and criticism for boldly exploring scandalous and sexual themes. And he would carve a niche for himself with a distinct “golden touch” that made his canvases shimmer.

Defined by a Golden Touch

Having a father and brother who were gold engravers undoubtedly formed Klimt’s close connection to gold, allowing it to permeate into his artistic vision. However, the gold in Klimt’s work went beyond aesthetics and carried deeper and more symbolic weight. Not only was gold a metaphor for luxury, spiritualism, and sensuality but as a leading figure of the Vienna Secession movement, Klimt perceived gold as a means of revolution. By turning to the unorthodox element in painting, he was denying traditional art norms.

Klimt’s “Golden Phase” came into realization around the turn of the 19th century. In 1903, Klimt took a pivotal trip to Italy where he was said to have fallen under the captivating spell of the glittering Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna. Seeking to capture that ethereal spirit in his own work, Klimt would begin using gold leaf in his paintings to imbue them with a distinct luminescence.

Some of Klimt’s most emblematic paintings from his Golden Phase include The Kiss (1907-08) and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907). Both pieces are stunning encapsulations of Klimt’s innovative technique and ability to creatively blend symbolic, erotic, and allegorical subjects against a backdrop that glows with the beauty of gold. In 2006, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer would be sold to businessman Ronald Lauder for a staggering $135 million, making it the most expensive painting ever sold at the time.

Klimt was unlike many artists of his time, refusing to adhere to prevailing trends and techniques. Instead, he dared to tread his own path by taking risks and facing criticism with resilience. He made calculated decisions about his style, use of symbolism, and subject matters that made his works instantly recognizable and ultimately, iconic. Klimt was particularly fascinated by the captivating aesthetics of decorative patterns and ornamental extravagance.

The Man Behind the Canvas

Although it’s well-known that Klimt never married, he allegedly fathered at least fourteen children. He had a reputation for being a ladies’ man and was known to have had affairs with many of his models and patrons. His models were a constant source of inspiration and companionship, motivating his sensual and erotic portraits. Viennese socialite Adele Bloch-Bauer, portrayed in two of Klimt’s most renowned paintings, was rumored to be one of his lovers despite the portrait being commissioned by her husband.

One of Klimt’s most famous muses was Emilie Flöge. The two had a close relationship for decades and were described to be “inseparable.” Flöge, an avant-garde fashion designer, is believed to have influenced Klimt’s artistic vision, particularly in terms of fashion and style. They collaborated on design and color for years, inspiring one another’s crafts. Flöge would produce designs that Klimt had made. And it’s been long-rumored that the couple depicted in a passionate embrace in the masterpiece The Kiss are Klimt and Flöge. Tragically, Klimt died in Vienna on February 6th, 1918 at the age of 55. He became one of the millions whose lives were claimed by the Spanish flu pandemic. When he passed, part of his estate went to Flöge.

Gustav Klimt’s artistic legacy and unrelenting pursuit of individuality continues to be celebrated and revered to this day. His paintings, characterized by intricate patterns, decorative elements, and sensual symbolism, remain iconic and continue to captivate audiences around the world.